- Topics

- Automotive industry

- Loss of jobs due to transformation

Automotive industry

Loss of jobs due to transformation

The switch to e-mobility will cost jobs. Small and medium-sized companies in particular will be hit. How politics can counteract this.

The switch to e-mobility will cost jobs. Small and medium-sized companies in particular will be hit. How politics can counteract this.

- Topics

- Automotive industry

- Loss of jobs due to transformation

The switch to e-mobility will cost many jobs

Background

To achieve climate targets, automotive manufacturers are putting more and more electric vehicles on the road. This is leading to a loss of jobs – not only in the automotive industry.

Overview

All studies quantifying the impact of transformation on employment conclude that the electrification of new car fleets will lead to significant employment losses in the automotive industry, and also in other sectors. Automotive suppliers will be hit particularly hard. Policymakers should try to minimize these employment losses, for example, by supporting the companies' retraining and continuing education programs. They should also recognize the employment opportunities that lie in the use of CO2-free e-fuels. It is equally obvious that a tightening of the CO2 target for 2030, as is currently under discussion, would require an even higher quota of electric vehicles and thus even greater employment losses.

An inevitable loss of jobs

The automotive industry is unreservedly committed to the goal of climate neutrality by 2050. Various technologies are available to achieve this goal. To achieve the interim CO2 target in 2030 (-37.5% compared with 2020), battery-electric powertrains take priority within this amount of time. At the same time, hydrogen and e-fuels will be established as further means of propulsion.

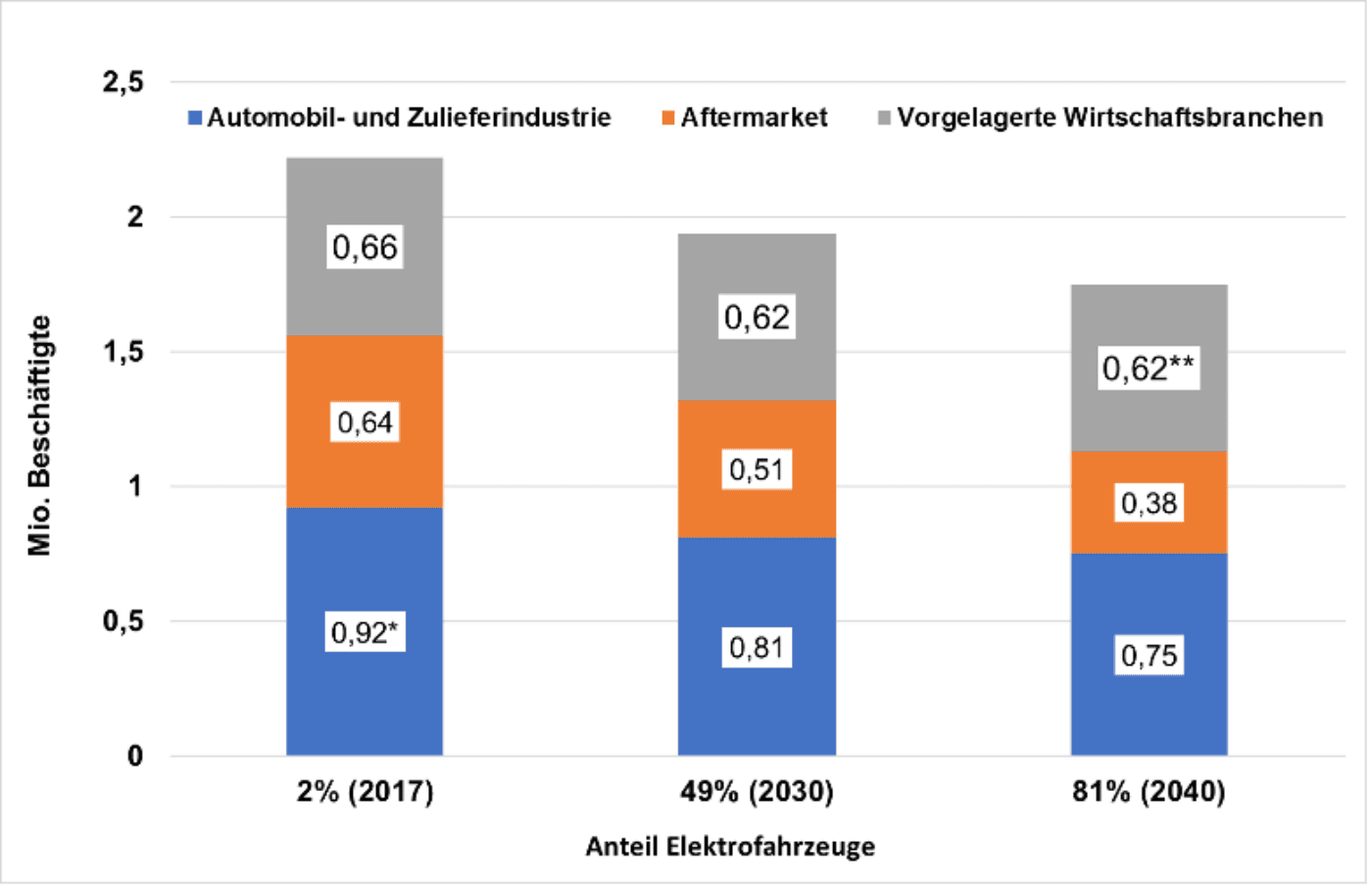

However, the switch to battery-electric powertrains will result in significant employment losses. This is the conclusion of all studies that have been published on this subject in recent years. One such study by the BMWI from 2019 ("Automotive value creation 2030/2050"; Roland Berger et al) puts the loss of employment at 170,000 employees in the automotive industry alone (manufacturers and suppliers) in the event of 80% of passenger cars manufactured being electric. This would correspond to a loss of more than 18% compared to the number employed in the automotive industry in 2017. This is true even taking into account that the electrification of the powertrain also creates new jobs, e.g., for the assembly of electrical components and their integration in the vehicle.

In addition to the employment losses in the automotive industry, there are also losses in those sectors upstream and downstream of the industry. For example, jobs are lost in the sectors "metal products, rubber and plastic products or foundry products." Jobs are also lost in the aftermarket, e.g., in auto repair shops, because electric powertrains consist of fewer components than conventional ones and are therefore more low maintenance. Overall, the BMWI study assumes further losses of 300,000 employees in the upstream and downstream sectors.

There are two reasons for the employment losses resulting from the electrification of the powertrain: First, far fewer parts are involved in an electric motor and correspondingly fewer parts need to be integrated with each other than in a piston engine (pistons, valves, gears, injection systems, sealing rings, etc.). Secondly, in the case of the battery electric drive, a significant part of the added value is generated outside the EU, namely in Asia. At least this is the case with battery cells, which are still being produced entirely abroad. However, German automakers are in the process of establishing their own domestic battery cell manufacture.

Loss of jobs particularly severe among automotive suppliers

Vehicle manufacturers are less affected by electrification and the associated job losses relative to their total gross added value than their suppliers, since the powertrain in an average compact class vehicle only accounts for around 30% of the added value in the overall vehicle. Suppliers provide about three quarters of all the parts in the piston engine; vehicle manufacturers produce the rest, assembling and integrating all the components. What previously proved to be a particular strength for many supplier companies – their high degree of specialization in the production of specific components for the powertrain – is now turning to their disadvantage. This is particularly affecting SMEs that do not have several technological pillars, unlike the larger suppliers. This high degree of specialization on the piston engine is reflected, among other things, in the fact that over 40% of suppliers state that they are not participating in the ramp-up of electromobility. In the past, specialization in the manufacture of specific components also had the advantage that companies were not in direct competition with each other. Now, they have to share an increasingly small market. Even a switch in production to components for electric drive systems would not change the fact that competition is intensifying, because an electric powertrain has far fewer components (and only the battery itself as the main component). Thus, in the future, more companies will have to compete for the manufacture of a component.

How can employment policy counteract this?

The fact that we are aiming for climate neutrality in the EU and in Germany by 2050 is a decision taken by society as a whole, and a task for society as a whole. In this respect, politics must also play its part in ensuring that the individual players can achieve their goal. In addition, it must guarantee that the resulting effects on employment are as socially acceptable as possible, i.e.:

- The job losses should remain as low as possible

- The interim targets for reducing CO2 emissions set by policymakers on the path to climate neutrality in 2050 must be designed so that as much of the reduction in employment as possible does not have to be achieved through redundancies and, instead, can be absorbed through the demographic development of the workforce (retirements). This should also be taken into account in the current discussion at EU level about a possible tightening of the 2030 fleet limits as part of the Green Deal. Overly ambitious CO2 savings targets limit the companies' ability to leverage the aging and retirement of their workforce for transformation and they also increase the risk of redundancies

- For employees in the automotive industry whose jobs are threatened by the electrification of mobility, policymakers must support the retraining and continuing education programs offered by companiesso that these companies can deploy as many of their experienced, proven employees as possible in the emerging manufacture of components for e-mobility

- Policymakers should recognize the employment opportunities offered by the use of e-fuels. These enable the climate targets to be met, even without the employment losses caused by electrification of the powertrain (piston engines can still be used). Further, there would be an increase in employment in the power-to-x industry (electrolyzers, conversion plants, CO2 separators.